So, what is ‘circularity’?

According to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, which promotes the principles of the circular economy, it’s an approach to business based on ‘designing out waste and pollution, keeping products and materials in use, and regenerating natural systems’.

The circular economy’s business models are based on the three Rs – Reduce, Reuse and Recycle. It’s about maintaining value, and not creating waste in the process. However, until recently, almost all industrial activity has followed a linear model based on Take, Make and Dump. The parallel in shipping is Design, Build, Operate and Recycle.

Global population growth and its impact on finite resources as well as the climate challenges ahead require linear business models to change. If they don’t, we could face a future where resources run out, the scale of waste management becomes impossible, and economic activity falters or stalls completely.

Taxonomy for sustainable activities…

Initiatives to tackle this crisis have already begun. The EU’s taxonomy for sustainable activities is one example. Launched during the pandemic, the European Commission said at the time: “The current Covid-19 pandemic has reinforced the need to redirect money towards sustainable projects in order to make our economies, businesses and societies – in particular health systems – more resilient against climate and environmental shocks. To achieve this, a common language and a clear definition of what is ‘sustainable’ is needed”.

Efforts to address taxonomy challenges around sustainability are well underway and a number of organisations have already embraced the circular economy in their business practices. The World Economic Forum cites IKEA, Adidas and Burger King as examples. They have business models that lend themselves relatively easily to the three Rs.

For heavy industries, which often rank amongst the world’s most energy-intensive, the challenge of circularity is more complex. These sectors include cement and steel production, as well as global transport, including airlines and shipping.

…in a marine context

A sustainable pathway to circularity as part of shipping’s decarbonisation process needs to be all-encompassing, going far beyond the propulsion system alone. It needs to take in the rest of the vessel, including the materials and processes during construction and recycling, say experts. It also needs to consider the interface between ship and shore and the avoidable harm that could be avoided by adopting circular systems.

Asset lifespan raises issues, too. Today’s ships mostly have operating lives of 20-30 years. The industry needs to re-examine this industry norm and question whether it still fits the circularity criteria. Specialists in the circular economy suggest that it probably does not, and that the sector should examine ways to minimise the creation of waste, to optimise material flows, and to reduce and reuse less carbon-intensive materials.

The first and third of shipping’s lifecycle processes – design and operation – are fertile arenas in which carbon-cutting initiatives abound and are already making a real difference. But the other two processes – shipbuilding and the materials that are used, and end-of-life asset disposal have changed little in decades. The magnitude of the process change needed to achieve circularity is likely to result in disruption to existing business models.

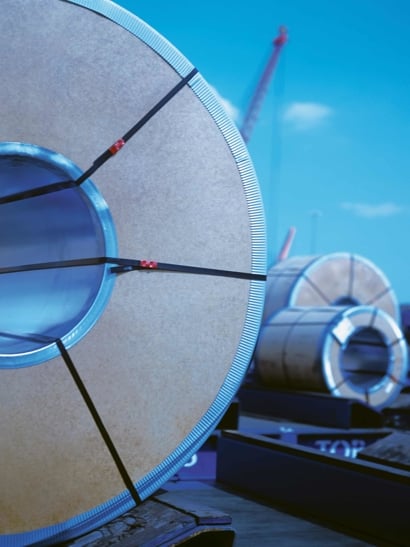

Steel resolve

The energy-intensive steel sector is proving to be a prime mover. Its initiative, SteelZero, is already making waves, with Maersk the first shipowner to join. Danish energy major, Ørsted, a founding member, has recently called on governments and businesses to do more to decarbonise the steel sector. In May, the company worked jointly with the Climate Group, a not-for-profit consultancy focusing on emissions reduction, to host the inaugural SteelZero summit, to launch a paper with recommendations for governments on how to boost the transition to ‘green’ steel.

Earlier, Maria Virginia Dundas, head of Strategic Environment Programmes at Ørsted, said: “While we have made industry-leading progress in reducing emissions in our energy generation and operations, we’re now at our next frontier of decarbonisation: the supply chain. At the centre of our efforts is steel, which makes up around half of the total climate footprint of our offshore wind farm projects”.

Speaking to Horizons, Maersk’s Capt Prashant Widge, Head of Responsible Recycling, said that ship building and recycling typically account for around five percent of a ship’s total lifecycle emission. Steel production using ship's scrap causes around five times lower emissions when compared to that of virgin-based steel production.

Cross-sector collaboration

Experts stress that although shipping often works in its own arena and maintains a distance from some other industries, a cross-sector approach is essential, not only within the individual sectors of marine transport - including designers, builders, and operators – but also with other hard-to-abate industries; not just steel, but also mining, and oil and gas.

Shipping’s finance providers also have a key role to play. The fact that environmental, social, and governance issues are high on their agendas is evident in the commitment of many funding institutions to the Poseidon Principles. This framework assesses clients’ credentials in relation to ESG issues, including emissions and decarbonisation strategies. It means financiers can assess the sustainability of the assets they invest in.

More recently, many of shipping’s major customers – cargo owners, traders and charterers – have established their own set of standards in the Sea Cargo Charter. Marine insurers have also taken up the baton from their counterparts in finance, adopting Poseidon Principles for insurers. However, none of these initiatives yet embrace the circular economy or circularity, and that is why the cross-sector collaboration is vital.

Under the radar

Samantha Bramley, Director, Environmental and Social Risk Management at Standard Chartered, emphasises this point. “There are certainly lessons to be learned from other industries”, she told Horizons. “They have been working for a long time to see how they can reduce their emissions and apply some sort of circular economy principles. Shipping has somehow flown under the radar, I think, because it is a hard-to-abate sector. But that’s not something it can afford to do for much longer".

LR's Ginger Garte agrees. "Embedding principles of the circular economy at every stage of a ship’s lifecycle is imperative," she told Horizons. "From construction to drydockings and repairs, to the use of new materials that don’t deteriorate over time or can be reused, to initiatives such as replacing many kilometres of steel piping on board ships with high-grade fire-proof plastic systems, which exist today".

More broadly, modular construction could enable key parts of a ship to be removed and replaced, thereby extending assets’ lives. The potential merits of new business models should be weighed up, Garte said.

Some shipboard components could be available on a subscription or lease basis, for example, with their manufacturers committed to refurbishing, reconditioning, and replacing parts at set intervals.

Taxonomy’s six objectives:

- Climate change mitigation

- Climate change adaptation

- Sustainable use and protection of water and marine resources

- Transition to a circular economy

- Pollution prevention and control

- Protection and restoration of biodiversity

The end game

Perhaps the most immediate obstacle – and one that could be tackled relatively promptly – is the lack of a plausible global regulatory framework on ship recycling. There are, for instance, almost no recycling facilities currently available for large commercial ships owned or operated in Europe to be recycled responsibly. Through a complex tangle of regulation and the classing of end-of-life ships as ‘waste’, it is not possible to export them from the OECD’s 38 country members to other nations outside the intergovernmental organisation. Yet most of the world’s recycling facilities are to be found in India, Bangladesh and Pakistan. No single recycling yard in that region has yet been approved under the EU Ship Recycling Regulation.

The Sustainable Shipping Initiative’s Andrew Stephens suggests that this could become “a significant barrier to handle what is predicted to be a waterfall of vessels to be dismantled in the coming decade, further limiting the possibilities to develop and progress potential for circularity.

“Other sectors and industries have faced similar challenges", he said, “and were able and willing to bring knowledge and awareness together to find solutions. The EU Taxonomy’s six principles… certainly add to the mix and amplify the need for alignment of the regulatory landscape around a common purpose of safe, responsible, no-harm, and circularity-based considerations through a ship’s lifecycle”. Furthermore, Stephens strongly suggests that “this is the perfect opportunity for shipping to embrace circularity. With new vessels being designed for shipping’s decarbonisation, now is a key moment for circular economy principles to be embraced by the industry”.