To comply with tightening regulations, ship operators must consider both the cost of compliance – such as fuel expenses and penalties – and emissions requirements. Regional regulations like FuelEU and EU ETS penalise greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and fossil fuel use, with additional IMO regulations on the horizon.

Now that these regulations are real rather than notional, it’s worth exploring what the next round of retrofits might be to meet them.

According to Santiago Suarez de la Fuente, LR Ship Performance Manager specialising in ship retrofits, “The most popular way to reduce fuel consumption and emissions at a stroke is to reduce speed.”

But even this simple measure requires physical adaptation because secondary impacts affect operation and systems performance, such as the propeller operating outside its highest efficiency.

Stephen Fewster, ING’s Global Head of Shipping Finance, and Treasurer of the Poseidon Principles, which accounts for 80% of the ship finance market and seeks to align their portfolio with the IMO decarbonsiation trajectory, and also sits on the LR Advisory Board, agrees. “The retrofits we have seen so far are relatively simple and inexpensive, to add silicone coating to the hull during dry docking, Propeller Boss Cap Fins (PBCFs), Becker Mewis Ducts, or in the case of container ships removing the bulbous bow to allow for reduced speed.”

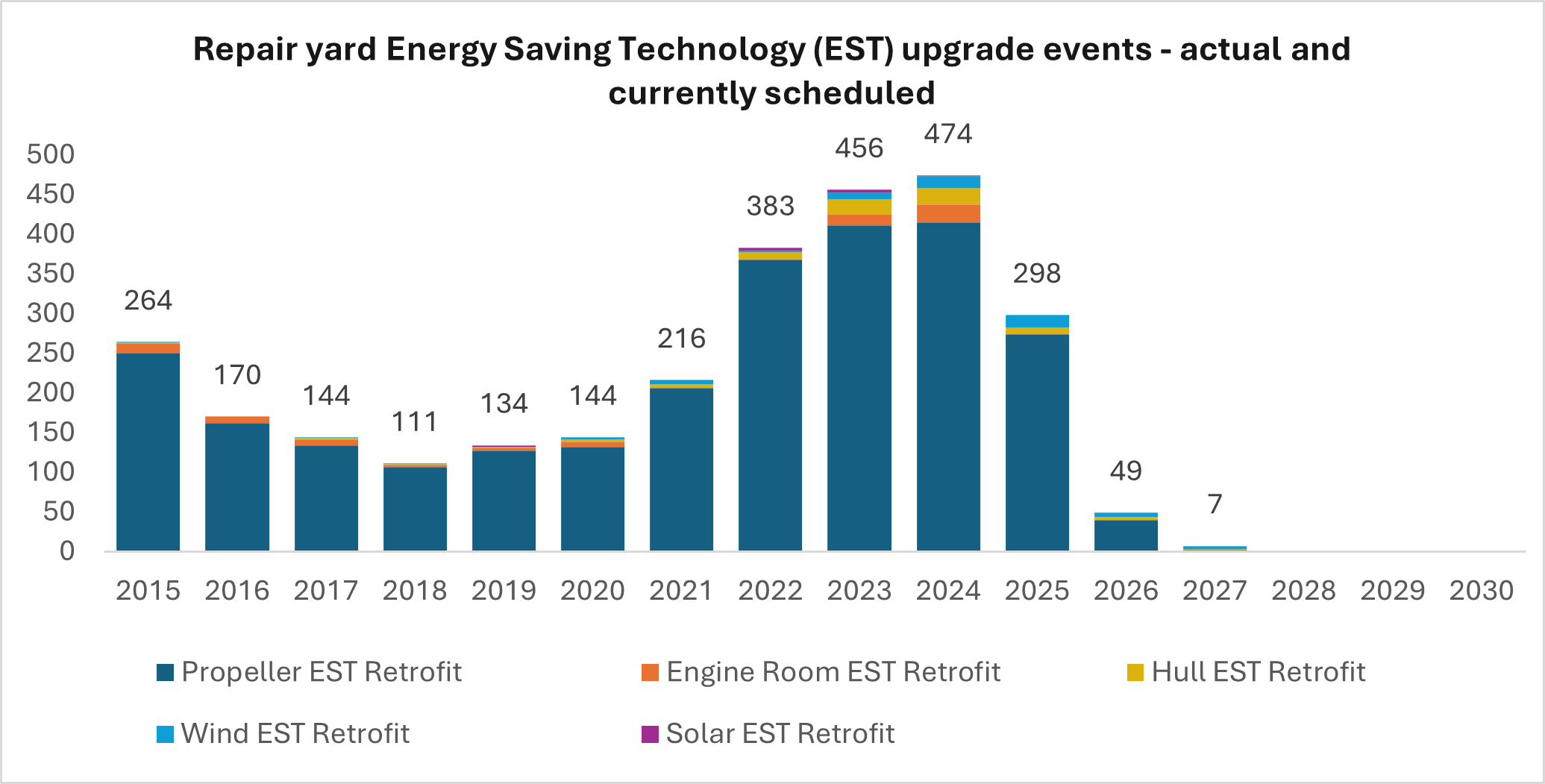

For these reasons, such retrofits will remain the most common type of retrofit in the short term. By using less fuel, penalties will be lower compared to ships that do not have these interventions.

Source: Clarkson’s Research, World Fleet Register, Retrofit Yards database, Feb, 2025

Novel propulsion

But there are limits. “Hydrodynamic devices like PBCFs can deliver between 0.50% and 0.75% efficiency, while fins can probably achieve around 1.00%,” says Suarez de la Fuente.

“This is good, but not enough when you need drops of 2% per year, relative to 2019, to follow the CII decarbonisation trend. Ship owners and charterers will need to start looking into more aggressive technologies or strategies,” he says.

“Wind can become dominant but not for every ship type. It is route-dependent. Certain routes will see big advantages but commercial and operational constraints can become a barrier for these technologies,” he explains.

Innovation and economies of scale will further bring down the costs of retrofits, but “The vast size of ships and variation in construction makes trials difficult – and expensive. Some technologies will not be scalable to larger or smaller ships or transferrable to different ship types,” he says.

Add-on technologies like wind are usually considered to be ‘transitional’, bridging the gap between fossil fuels today and green or synthetic fuels in the future. But Fewster says this is not the case.

“Technologies like wind and other fuel saving devices are not transitional technologies. Today they reduce fuel usage and therefore emissions but as we transition to green fuels, these technologies will still reduce your fuel bill. They are here to stay,” says Fewster.

New fuels

“When considering new fuels, we must create a distinction between ‘ready’ and ‘capable’ vessels,” says Fewster.

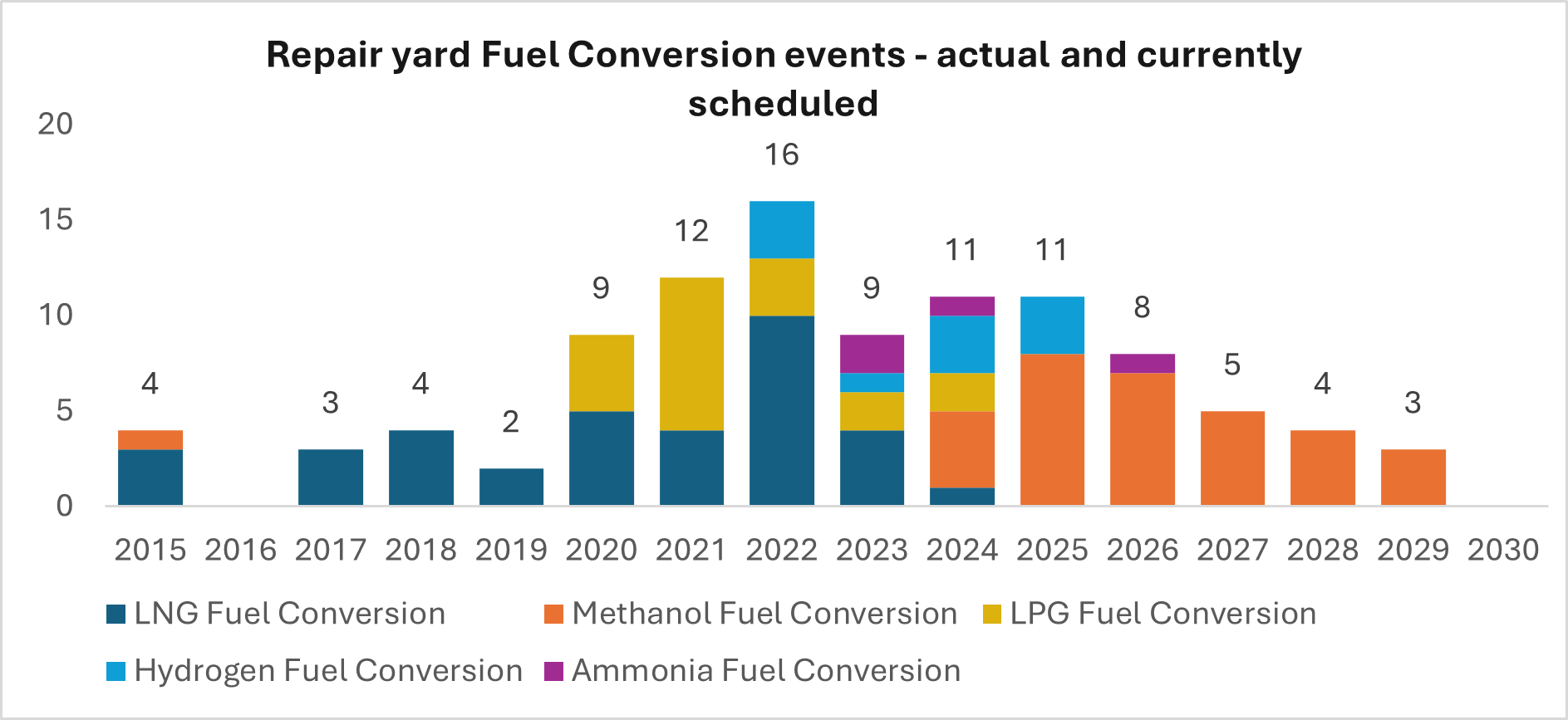

Source: Clarkson’s Research, World Fleet Register, Retrofit Yards database, Feb, 2025

“If a ship is new 'fuel-ready’, this is the owner building in optionality which could be to leave space for a tank or piping. The ship is not able to run on that new fuel but could be retrofitted in the future.

“Then there is new 'fuel-capable’. These ships are already able to use either heavy fuel oil or a new fuel like methanol, but they are held back by the availability of the fuel. Many dual fuel ships run on both heavy fuel oil and LNG because there is good availability of LNG. For other fuels like ammonia, there is not yet this availability.

“The next round of retrofits will be to evolve those ships that are methanol- or ammonia-ready to be methanol- or ammonia-capable,” he says. Clarkson’s research backs this up, showing scheduled fuel retrofits to be dominated by methanol, with hydrogen and ammonia.

Scenario projections to 2050 show LNG to be consistent, with fossil fuels displaced by battery, hydrogen, ammonia and methanol according to Clarkson’s Research.

Falling fuel prices?

Regulatory penalties for ships running on fossil fuels imposed by the EU are designed to be low initially, slowly increasing until 2035 when there will be much sharper penalties.

Now there is talk of falling fuel prices, could this distort the calculations owners and operators make?

Fewster and Suarez de la Fuente agree that if the fuel price does drop this will delay the overall transition because the costs of penalties will be offset by the reduced price of fuel.

“But it won’t stop it,” says Fewster. “Fortunately, we do have an international regulator, and we have CII ratings to show how well ships perform. Regulation and consumer demand through Scope 3 emissions will be the main drivers for decarbonisation,” he says.

Accelerating retrofits

Suarez de la Fuente says fossil fuel subsidies should be reduced to level the costs of fossil fuels and new fuels. Fewster has a different take, to actively penalise fossil fuels. “I would like to see a carbon levy, so there is an equivalence in costs between fossil and new fuels. It won’t then matter if the oil price drops – the levy will even that out,” he says.

Then, Fewster wants to incentivise the energy transition by increasing benefits to proactive owners and operators. “I would like to see tax relief from financial regulators and governmental bodies. If we have capital relief on financing green ships, we could offer a lower cost of funding. We have sustainability-linked loans already. If ships meet decarbonisation targets, we can slightly lower the rates, or slightly increase them if they fail to meet those targets. With capital relief, those incentives could be bigger,” he says.

Both agree that the biggest threat to energy transition is inertia, and for a generation of decision-makers about to retire, it really is someone else’s problem.

The next generation of decision makers need a new kind of mindset that is more holistic, cooperative, to balance the priorities of the sector and protect the environment.

Global warming is not slowing down. If banking institutions, global companies and countries with large greenhouse gas footprints backtrack on their commitments then the challenge to 2050 will be steeper, more expensive and adaptation strategies will need to come into play more quickly than anticipated.

A difficult challenge, but the right thing to do, particularly as we have a banking regime to back the investment needed.

Funding the energy transition

Launched in June 2019, the Poseidon Principles member banks now represent 80% of the shipping finance portfolio. Fewster explained some of the considerations taken by ING when funding the maritime sector.”

“There is a two-tier industry. There are those owners who are ahead of the curve and doing what they can to reduce their emissions. Then there are those that want to run their ships as hard as they can for as long as they can.

“At ING we have developed a platform called Green Knot which enables us to assess the carbon intensity of every ship we finance and contains data from the 1200 ships in our portfolio. Other financial institutions who are members of Poseidon Principle will do something similar. We look at the creditworthiness of the borrower but importantly we receive or can calculate the AER data for the ship.

“From this we calculate where it is against IMO targets and whether by financing the vessel and retrofits we assist in helping reach that target. This plays an important role in whether we provide finance.

“If the vessel is above the target, that doesn’t mean we won’t provide finance but we will have a discussion with the client to see what steps can be taken to improve the performance. If they are open to this, we will look to work with them but for those who are not open ‘yes’, they will have to start looking at the alternative financing means.”