As part of our recent webinar following MEPC 83, two of LR’s regulatory and advisory experts explained that the proposed mid-term GHG reduction measures, while challenging, can also present commercial opportunities if properly managed.

Despite the complexity, cost, and potential disruption, the webinar made clear that inaction is not an option – and that proactive engagement with the draft regulations could help shipping companies unlock competitive advantages as the maritime sector moves towards the IMO’s 2050 ambitions of net-zero GHG emissions from the shipping sector.

Hosted by Lucy Dibdin, LR’s External Communications Director, the webinar was divided into two parts. Initially, Andy Wibroe, Lead Regulatory Specialist, explained the framework, revealing that tank-to-wake emissions will be replaced by well-to-wake assessments, and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions will now include methane and nitrous oxide.

The regulations, in draft form until their adoption at the 2nd Extraordinary Session of MEPC in October, have been drawn up to prepare a pathway for a steady reduction in ship emissions. These will be calculated from all emission sources and totaled to give a ship’s GHG Fuel Intensity, GFI, a measure of emissions per unit of energy – specifically, grams of carbon dioxide equivalent per megajoule.

The benchmark against which ship emissions will be measured under the proposed regulations is a set of target GFIs reducing year on year from a baseline of 93.3 gCO2eq/MJ, a figure that represents international shipping’s average emissions of carbon dioxide equivalent in 2008.

Two reduction trajectories...

There will be two so-called reduction trajectories linked to 2023 IMO reduction ‘check points’ with a base target aligned with the ‘base’ checkpoints in IMO’s 2023 GHG Reduction Strategy of 20% reduction by 2030 and 70% reduction by 2040, and a direct compliance target aligned with the ‘striving for’ checkpoints in the Strategy of 30% reduction by 2030 and 80% by 2040, all compared to 2008 levels. These trajectories are initially set between 2028 and 2035, with targets between 2036 and 2040 to be determined by January 2032 and a place holder of a 65% reduction in 2040 for the ‘Base’ target.

…and two compliance deficits

The workings of the regulations is that a ship’s attained GFI in a given year is compared to these two targets. A ship that does not meet the direct compliance target will experience ‘Tier 1’ compliance deficit whereas a ship that does not meet either the direct compliance target or base target in a given year will experience both ‘Tier 1’ and ‘Tier 2’ compliance deficits, all of which must be balanced in order for the ship to trade.

Conversely, a ship that supersedes both targets will experience a compliance surplus which may be traded with under compliant ships on an open market.

LR’s Wibroe emphasised the importance of ensuring that a ship meets the targets in order to generate Surplus Units (Sus) which have a maximum value of $380/tonne of CO2 equivalent equal to the Remedial Unite (RU) for ‘Tier 2’ compliance deficit. These SUs can then be used to offset other ships’ Tier 2 Compliance Deficit, or be ‘banked’ for up to two years into the future.

Where ships do not manage to meet the targets, ‘Tier 1’ deficit must be balanced by purchasing RUs at the Tier 1 rate of $100/tonne CO2 equivalent from a central IMO GFI Register. Ships that experience ‘Tier 2’ deficit can either purchase RUs at the Tier 2 rate of $380/tonne CO2 equivalent, obtain SUs from a ship that is in direct compliance in the same year, or use ‘banked’ SUs from a previous year. However, Wibroe cautioned that due to the expiry of SUs 2 years after the year they are issued may mean they have expired before a ‘Tier 2’ deficit is experienced meaning banked units may not be useable in all scenarios.

All ships will have to pay an administrative fee for the operation of the IMO GFI Registry which will be established to oversee and manage ship compliance. It will:

- credit ships exceeding the Compliance Target with Surplus Units worth $380 each

- issue Remedial Units of both types to ships that are not compliant and collect relevant payments

- manage the ‘bank’ of Surplus Units in a ship’s account

- record the transfer of Surplus Units between ships

After Wibroe had explained the intended framework of the IMO’s mid-term measures, his colleague Jack Spyros Pringle, Head of Energy Transition Advisory, outlined both the challenges and the opportunities that owners, operators and charterers are likely to face from 2028. It was clear from what he said that doing nothing is definitely not an option.

Strategic plan essential

After outlining the consultancy and advisory services that LR is now offering, Pringle explained that owners’ choice of compliance strategy will have a direct bearing on the financial outcome. The first stage of preparing a strategic plan will be to assess a ship’s current emissions profile and conduct a gap analysis to identify how its performance could be improved over the remainder of its operating life.

A second stage would then be to examine the costs and benefits of various ‘levers’ to cut ship emissions. These could include operational efficiencies such as the optimisation of speed and waiting times, assessing the potential for using a mix of fuels with lower overall emissions such as biofuel, for example. Investment in energy saving devices such as wind assisted propulsion technology, modifications to the propeller or rudder, and air lubrication could be another option.

A third stage would be to decide on a compliance strategy. Pringle outlined two of these: one would be based on minimising capital costs while ensuring regulatory compliance. A second, more ambitious strategy would be to aim for ‘operational excellence’, maximising vessel performance and commercial flexibility and, of course, ensuring regulatory compliance.

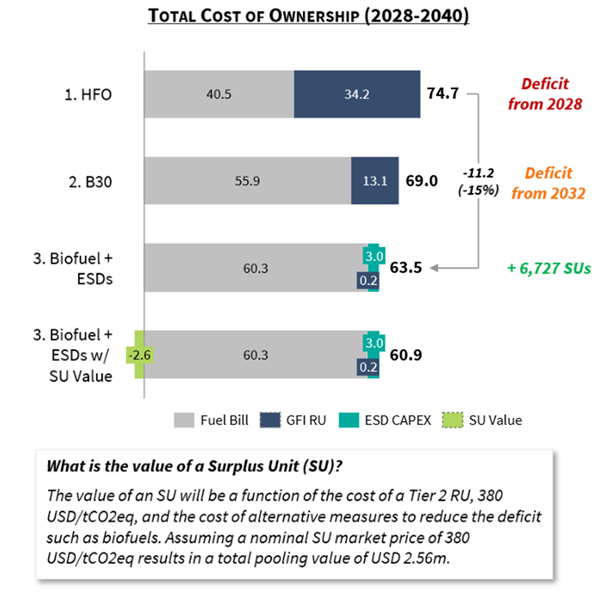

Although the fuel costs for the Suezmax tanker between 2028 and 2040 are lower when it is operating on heavy fuel oil, the vessel will generate significant additional costs from the Remedial Units required to offset the high-emission fuel. Adopting a more strategic approach by phasing in more expensive biofuels and investing in ESDs would ultimately reduce the ‘total cost of ownership’ by at least 15% over the period.

He then emphasised the importance of a sound emissions reduction strategy over the coming years by comparing the ‘Total Cost of Ownership’ of various strategies. Applying them to an Aframax tanker consuming 6,000 tonnes of heavy fuel oil a year, he first demonstrated that the vessel would be in a Compliance Deficit from day one. In fact, it would be generating Tier 1 deficits ($100 each) and Tier 2 deficits ($380) from the outset.

Cheap fuel will be the more expensive option

On the other hand, by using a fuel mix including biofuels, the tanker could generate Surplus Units in the early years of operation. And if the volume of biofuel were increased steadily over time, this date would be pushed steadily further back.

If the tanker’s owner chose to adopt a strategy of ‘operational excellence’, the tanker could avoid the accrual of Compliance Deficits and the need for its owner to buy any Remedial Units between 2028 and 2040. In fact, he demonstrated, this proactive approach would reduce the total cost of ownership by 15% over the period and more than 18% if the financial benefit from Surplus Units is also included.

The conclusion is that with appropriate analysis and advice, and despite the formidable decarbonisation challenges that global shipping faces over the next 25 years, an early and proactive emissions-reduction strategy will yield substantial financial benefits. At the least, it will ensure the best possible outcomes in complying with steadily tightening emission regulations up to 2050.