Bringing together a multitude of technologies is an option to reduce energy usage and greenhouse gas emissions from vessels, and is available right now. But can we do more than just ‘stack’ new technologies on to existing designs? How will ship design change in response to the future business models of a decarbonising maritime industry?

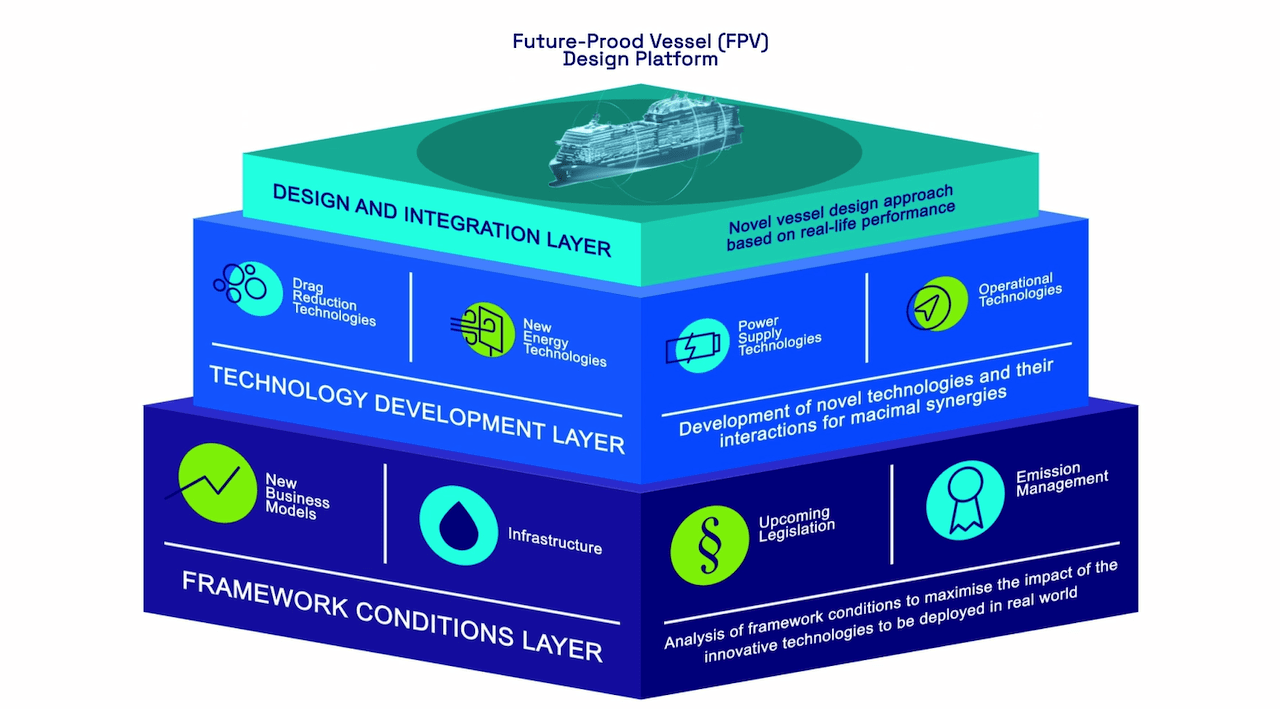

That is what the CHEK project is examining. It will develop and demonstrate two bespoke vessel designs; a hydrogen powered cruise ship, and a wind energy optimised bulk carrier. The group of partners involved are proposing to develop a unique Future-Proof Vessel (FPV) Design Platform to ensure synergy between the novel technologies and the vessels’ real-world operation, rather than just sea-trial performance.

Yildiz Williams, a Lead Marine Consultant at LR, is a chartered naval architect with extensive experience in marine advisory in environmental legislation and sustainability. She is the technical lead for LR’s contribution to the CHEK project and says that questioning the business models of how ships are owned and operated have not been necessary, until now.

The ships and novel technologies being fitted to them are more expensive than before. The investment at the build stage of a new ship is of more benefit to the charterer than the owner and looking at new, radical business models are one of the answers to how we increase the uptake of novel technologies.

"Finance-sharing models are already being tried in maritime. The bulk carrier under the CHEK project is doing just this with two sails. One is funded by the European Union as part of the CHEK project, the other is paid jointly by the charterer and shipowner."

Performance guarantees

Under a performance guarantee model, the providers of new novel technologies give guarantees against downside technology performance risks. “These guarantees incentivise a technology provider to ensure that their machinery meets, and even exceeds, an agreed baseline,” Williams explains, “If it doesn’t there will, of course, be penalties.”

How do they work, and what is the key to their success? “For performance guarantees to work it is important to establish the baseline performance of a vessel prior to the addition of new technologies, and to establish the true benefit a manufacturer is willing to agree their technology can bring,” explains Williams. “At the moment, there are a variety of novel technologies which are available on the market, and they have a wide variety of claims in the amount they can reduce fuel consumption and GHG emissions. Performance guarantees give greater confidence, from owners, operators and charterers through to regulators and legislators, on the claims made by manufacturers.”

After establishing a baseline performance comes the next stage in the process; the guarantee. “Here, we are looking at a contract,” says Williams, “which sets out exactly the reduction in fuel consumption and GHG emissions against the standard baseline of the ship. As per the Rolls Royce ‘Power-by-the-Hour’ model when the technology is working to the agreed standard, the ship user is saving fuel and GHG emissions, and the manufacturer is earning money.”

Sharing the costs to get the benefits

To make performance guarantees a success, Williams suggests looking at the initial purchase and build of a ship and how this is financed.

“Under the current business models, we see a ship purchased by an owner, with the end charterer being the one who is liable for the payment of fuel to run the vessel. There is little incentive, therefore, for an owner to purchase and install technologies at an additional cost, which will reduce the fuel bill of the charterer.”

For this reason, we also need to explore finance sharing models. “Under this model, we see all those who benefit taking a stake in the financing of fuel consumption and GHG-reducing technologies. Sharing the costs, to share the benefits.”

This is already being applied in the real world. “The CHEK project is doing just this,” Williams explains. “The bulk carrier has two sails. One is funded by the European Union as part of the CHEK project, the other one is paid jointly by the charterer and shipowner.”

“In the past, an arrangement like this would have been unheard of. However, with the ability to increase efficiency, and reduce costs and GHG emissions, charterers contributing to the financing of additional technologies is absolutely a model for the future.”

Williams concludes, “the real-world implementation of performance guarantees and finance sharing models shows the commitment from stakeholders across the industry to testing, implementing and operating new technologies to reduce GHG emissions.”