For more than 260 years, we have shown relentless curiosity to discover our clients’ challenges and to work together to identify the best solutions.

We enable better safety, technical, operational and business performance in the Maritime sector, serving clients across the globe.

Our people are trusted and respected worldwide for their deep technical expertise and professionalism. We value and build strong relationships and personal connections. Our innovation is grounded in listening to our clients and colleagues. This is why Lloyd’s Register (LR) inspires confidence as a trusted adviser, supporting clients with the challenges of today and tomorrow.

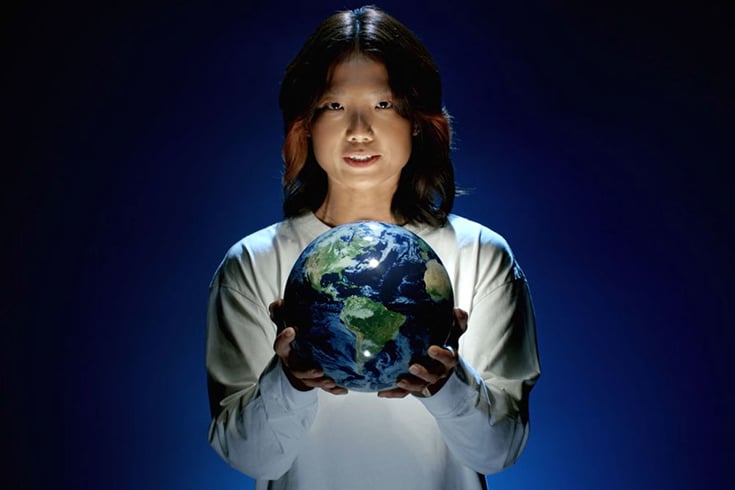

As humanity faces some of its greatest challenges, including population growth, climate change, and rapid technological developments, there is an urgent need to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. In this pivotal race, the ocean is a vital resource that plays a crucial role in meeting these challenges.

Lloyd's Register Foundation and Lloyd's Register collaborate to positively impact the ocean economy by partnering with others to enhance the skills of seafarers worldwide, promote community resilience, and facilitate a safe and equitable transition to zero-carbon fuels.

- Lloyd's Register

- Lloyd’s Register Foundation

- The Decarb Hub

- Lloyd's Register OneOcean

We are a leading provider of classification and compliance services to the marine and offshore industries, helping our clients design, construct, operate, extend and decommission their assets safely and in line with environmental expectations.

In the drive for efficiency, sustainability and resilience in the ocean economy, our technical and business advisory services enable businesses to reach their full potential and achieve a competitive edge – now and into the future. We offer our clients advice, support and solutions during every stage of the asset lifecycle across the maritime value chain.

In the race to zero emissions, our solutions, technical expertise and industry-firsts will support a safe, sustainable maritime energy transition.

Lloyd's Register Foundation was established in 2012 as an independent global charity with a mission to engineer a safer world.

The Foundation shares this mission with Lloyd’s Register. Both organisations are committed to keeping people safe and where appropriate, work together on initiatives which foster industry collaboration and focus on action-oriented solutions for the benefit of society, such as the Maritime Decarbonisation Hub which focuses on creating safe, sustainable pathways to a zero-carbon maritime industry.

The Foundation focuses on the most pressing global safety challenges, establishing the best evidence and insight to understand the complex factors that affect safety, funding interventions which tackle these challenges and building global coalitions for change.

The Decarb Hub is an independent, not-for-profit social purpose organisation, working towards our vision of a safe, sustainable, and human-centric decarbonised shipping industry for the benefit of society.

Formed in 2020 with a grant from Lloyd’s Register Foundation, and in partnership with Lloyd’s Register Group, we are an evidence-led research and action unit. Our team of specialists in economics, fuels, risk & safety engineering, human factors, and analytics deliver research, insights, and implementation pathways to future fuels across the maritime supply chain.

Lloyd's Register OneOcean is the digital solutions platform providing actionable intelligence to maritime professionals worldwide.

As an integral part of Lloyd’s Register, we exist to create a seamless connection between each and every vessel and voyage, stakeholder and supply chain to truly unite the digital journey between ship and shore.

Our easy-to-use, secure platform brings market-leading compliance, management and performance software together to help shipowners, operators, charterers and crew drive stronger growth and efficiency in a safe, sustainable way.

With years of global maritime expertise, innovation and experience across 22,000 vessels, we aim to be the most trusted digital platform for enhancing people, profits and the planet.

Learn more about Lloyd's Register

Our values - the qualities underpinning our culture

- We care

- We share our expertise

- We do the right thing

- As your trusted advisers, we always strive to:

- We care about the safety of everyone.

- We respect each other and the wider communities we work in.

- We’re passionate about giving back to society, leaving the world a better place than we found it.

- We care about each other, our clients and the environment.

- We strive to be the leaders in our profession with unparalleled expertise.

- We’re committed to quality and work together to find the best solution.

- We’re inquisitive and curious and never stop learning to further our knowledge.

- We share our expertise with each other, with our clients and with all of our stakeholders.

- We’re independent and impartial.

- We show integrity in everything we do.

- We’re brave and courageous and we never compromise on standards or safety.

- We do the right thing in every situation.

- To bring our technical expertise and a flexible approach to address your challenges.

- To treat you as a valued client, tailoring our support to your needs.

- To keep our promises and be easy to work with.

- To be ready to deliver service where in the world you need us.

- To share our industry knowledge proactively to inspire progress.